“The possibility of a different world is the point of art.” Brian Eno

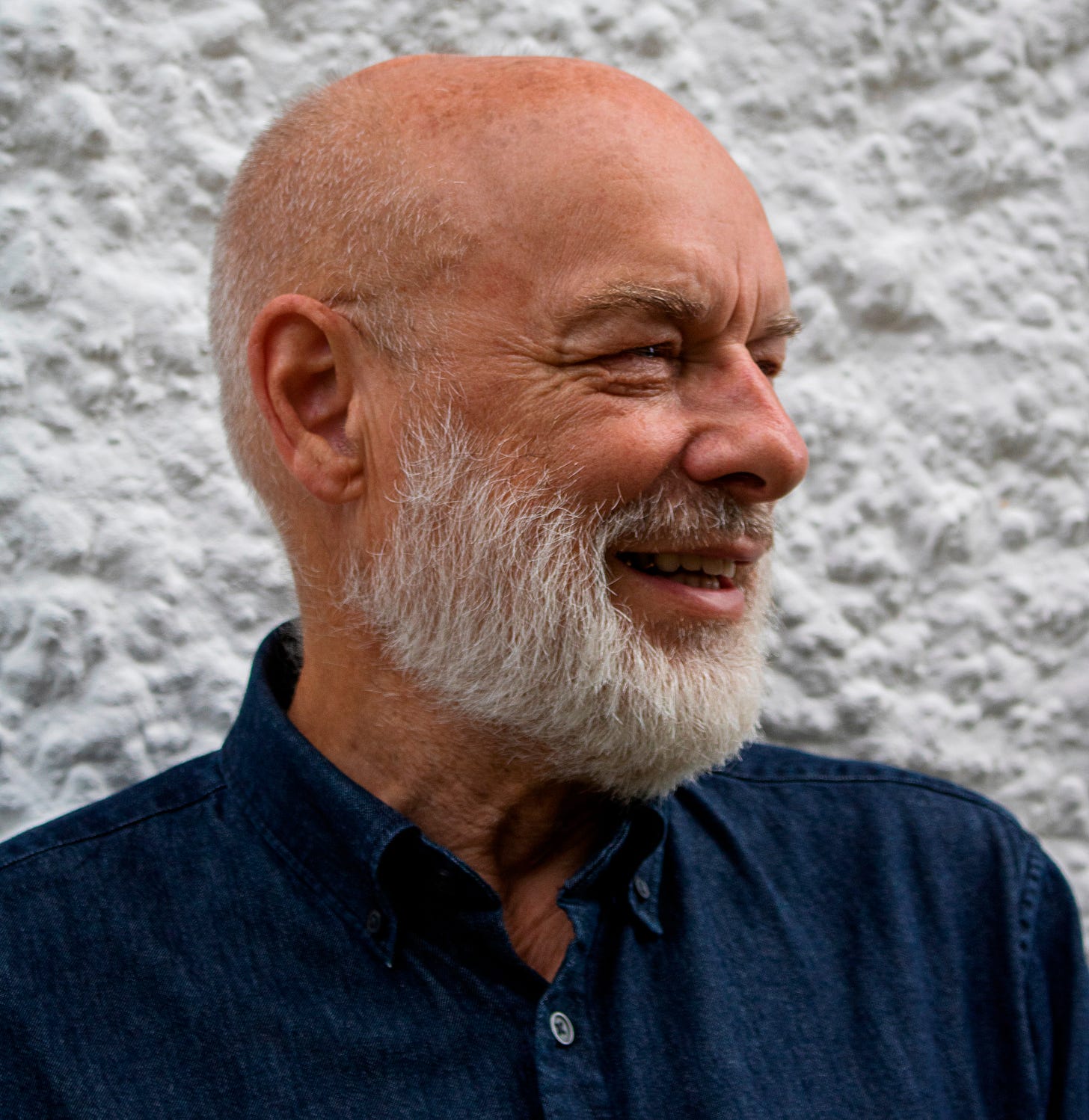

In the studio with Eno - legendary music producer, artist and activist

Brian Eno is tired. He’s been in Manchester for the past week curating the Fête of Britain, a four-day cultural takeover challenging people to rethink politics in the UK. This morning he was the keynote speaker at a music conference. And now he’s back at his West London studio to talk to me. It would be a lot for anyone, let alone a 75-year-old. “Thanks for giving me your time - I’m sure this is the last thing you feel like doing this afternoon,” I say as we shake hands. “The second last” he jokes, his gold front tooth catching the light. “The last is not surviving the day.” Given Eno has been known to fall out with journalists who bore him or ask too many questions about Bowie, I rather feel the same.

Composer, music producer, visual artist, theorist, activist - Brian Eno is one of Britain’s most influential cultural figures since The Beatles. He twiddled synths in 70s glam rock band Roxy Music, stealing the show in leopard-print and gold lamé, and has since collaborated with everyone from Talking Heads, David Bowie and U2 to Coldplay and Paul Simon. He also pioneered ambient music (his groundbreaking ambient album, Another Green World, is 50 this year) and has consistently been leaps ahead of the zeitgeist. Not bad for a man who, by his own admission, ‘doesn’t really play any instruments’ and can’t read music.

His latest endeavour is Earth Percent, an organisation which aims to ‘unleash the power of music in service of the Planet’ and raise $100 million for climate causes by 2030. As part of a BBC radio documentary I’m making about Earth Percent, Eno has agreed to this interview at his studio, an airy, loft-like mews house in the heart of Notting Hill. There are shelves spilling with books, a sink, a couple of sofas. Two of Eno’s famous lightboxes hang on the whitewashed brick walls. More stylish academic than louche glam rocker, Eno - a slender, elfin figure - wears a turquoise shirt and navy corduroy jacket.

His assistant makes us tea (rooibos, no sugar) and we head into a small room off the main space, where two computer monitors and an M-audio keyboard sit on a standing desk framed by a pair of retro wooden speakers. “I’ve got 9,978 unreleased tracks” Eno says, switching on the monitors. “Often I make something, put it in the archive and forget about it for years. So at the moment I’ve set this up so all these tracks play in a continuous stream of 5 second sound bytes. I listen to them when I’m washing up, or sweeping, and then dash back in here and mark any I like.” He selects a few tracks and we stand side by side listening to short bursts of music: birdsong, drone noises, something that sounds like a train, which he tells me he wrote on the Eurostar whilst speeding through northern France. “It’s a bit hectic, not recommended for casual listening” he says with a wry laugh. His calm, genial air has soothed my oh-my-god-I’m-interviewing-Brian-Eno nerves, my chances of surviving the day improving by the minute.

Next Eno shows me how he’s programmed a piece of software to randomly select three of these unreleased tracks, collaging them together to create an entirely new piece of music. “Now this is a good piece, I can tell I can make something out of this” he says, as ambient, cinematic sounds fill the room. It’s the sort of music that should come with an advisory to listen to lying down, between a large pair of speakers. “I can see night time, a big, flat landscape, some sort of insect life.” He speaks quietly and eloquently, his voice as soothing as the music. “As soon as I start seeing pictures in my mind, when I can see a landscape and feel the temperature of the place, I know a piece of music is right. But I don’t wait for this to happen, I just keep working until I feel something. As Picasso said: inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.”

I find this fascinating - that Eno both feels and sees music. But this is a man who thinks and feels deeply, and whose feelings have very much directed his artistic output. As we listen to more samples he tells me how, as a child, he spent a lot of time alone - walking, dreaming, drawing. “I'd sit and do drawings on my little sketch pad and I noticed that if you sit still for five minutes things stop noticing you, suddenly there are grass snakes wriggling by and birds sitting close to you. And that was a lesson to me - that if you shut up, the rest of the world speaks.”

Much of Eno’s work connects to this sense of aloneness he felt as a child, and the empty, melancholic landscapes of his Suffolk upbringing. Marshes. Dark woods. Open fields. But it was this solitude that taught him to be still, to listen, to feel. “Artists are basically feelings merchants” he says. “Feelings are the beginning of thinking, they’re at the root of things, and that’s the material we artists work with.”

In recent years Eno’s feelings about nature and the state of the environment have become central to his artistic output. Increasingly aware that governments aren’t doing enough about the Climate and Ecological Emergency, in 2021 he founded Earth Percent. The idea was to create an interface between the music industry and the environmental movement, and encourage artists to give a percentage of their income to climate causes, with Earth Percent as the middleman. “There's a huge amount of money flowing through the music industry, more than ever before - I mean, have you bought a concert ticket lately?” Eno says. “The idea is to siphon off some of that money and divert it to people who are helping to protect our future. And I’m pleased to say it’s working.”

So far over 250 artists and music companies have pledged their support to Earth Percent; among them Coldplay, Michael Stipe, Anna Calvi, Aurora, Fred again, Donna Grantis, Louis VI and Sam Lee. Some donate a percentage of their tour income, while others divert a portion of their recording royalties. That money - well over a $1 million so far - then helps fund organisations such as Client Earth, Oceans & Us, Music Declares Emergency and the Youth Justice Climate Fund.

Eno wasn’t always an activist. Until the Balkans conflict of the 90s, when he became involved with the charity War Child, he thought it wasn’t the job of artists to get involved in such things. But on seeing the potential impact he changed his mind. Since then, his art and activism have been closely aligned, with Eno continually asking himself whether what he’s doing ‘is worth doing at all?’ This, he says, stems back to his late teens, when a girlfriend's mother asked him why such an intelligent young man was wasting his time at art school. The comment stayed with him, and has led to a lifelong questioning of the point and power of art.

As fascinating as it is to see Eno at work in his studio, what interests me most - and what’s really stuck with me since meeting him - are his reflections on feelings, the role of artists as activists, and the need to create art and music that make people feel strongly enough to act. At one point during our conversation he says: “The possibility of a different world is the point of art.” It’s a comment I’ve thought about a great deal since.

Donna Grantis (formerly Prince’s guitarist, nonetheless), Aurora and Louis VI, who I also interviewed for this documentary, all echoed Eno’s sentiments about the power of art to inspire positive change. “Where words have failed, where facts and science haven't quite triggered people’s emotions enough to make them do something, art has this phenomenal way of cutting through” rapper and producer Louis VI told me when we met at his Dalston studio on a sweltering August day. In the wake of the US election it feels like art has a more important role to play than ever. As Nina Simone said: “An artist’s duty is to reflect the times.”

Back in Eno’s studio, I ask him to what he credits his enduring success. “I think the most important factor in every artist's success is a level of obsession, of just refusing to let something go. You have to be obsessed to the point of being prepared to fail quite often, and not give up.”

A few minutes later his assistant appears, tapping her watch to indicate our 45 minutes are up. We shake hands again, I thank him (probably a little too profusely) and turn to leave. At once he returns to his desk. There are five minutes until his next meeting - who knows what Brian Eno could achieve in that time.

BEFORE YOU GO….

My radio documentary about Eno airs on BBC World Service at various times tomorrow, the 26th of November. It’s also available as a podcast on BBC Sounds. Do let me know what you think of it in the comments below. I’ll be doing a live chat thread for paid subscribers here on Substack at 14.30 tomorrow, for anyone who’d like to chat about Eno, Earth Percent or anything else in the documentary.

I’ve decided to introduce paid subscription options for this newsletter. I’ve set the subscription at the lowest point Substack allows (£3.50 a month, which is a pound less than the average price of a caffè latte in the UK at the moment) and have made it as accessible as possible. I’ve also introduced a Founding Member option which, for £150, gets you lifetime subsciption to the newsletter, a signed copy of one of my books and a 45 minute 1-1 Zoom session on any subject you choose; be it a writing tutorial, broadcasting advice or a chat about an expedition you’re planning. Thank you so much if you do become a paid subscriber - your support will enable me to write and explore more.

It’s that sleigh bells time of year again….. if you’d like to buy someone a signed copy of Land of the Dawn-lit Mountains for Christmas, click here! Frustratingly I’m waiting for a reprint of A Short Ride in the Jungle and won’t have more copies until the New Year.

If you’re a bird person, you might like my recent report from Georgia on BBC Radio 4’s Rare Earth. It’s a story about raptors, migration and the perennial battle between nature and development. And if you’ve already listened, below is the bathing owl video I mentioned…

Last month I wrote a post from Tbilisi, Georgia, a few days before the election which, as many of you know, was ‘won’ by the pro-Russian ruling party Georgian Dream. Of the many articles written in the wake of the election, this piece in The Guardian by Natalia Antelava was the most insightful. As she rightly wrote: “The losers aren’t just the Georgian opposition and their supporters but everyone who believes in the value of freedom.”

That’s all for now. I’ll be back in December with a story from Georgia, plus a bonus post on my favourite books of 2024.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Under the Hawthorn Tree with Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.